The Mediterranean case: mooring with lazy lines

Most collisions between recreational boats occur during harbor maneuvers.

Fellow sailors, here’s a recap of the basics of engine maneuvers... Practice them until you master them perfectly!

The propeller wash effect, friend or foe?

A fundamental element of engine maneuvers, the propeller wash effect is the lateral influence of the propeller’s rotation on the boat’s movement. It is always stronger in reverse gear and must be considered during maneuvers.

The principle

A propeller works due to the inclination of its blades. This inclination causes every propeller to push water obliquely.

In forward motion, the propeller pushes water onto the rudder, which, through its orientation, compensates for the lateral effect of the propeller.

In reverse, the propeller pushes water forward, and there’s no rudder to reduce this lateral effect: the boat moves diagonally until the speed is sufficient for the rudder and keel (or centerboard) to engage the water and allow steering.

Thus, the propeller wash effect is strongest in reverse. You must always account for this during engine maneuvers.

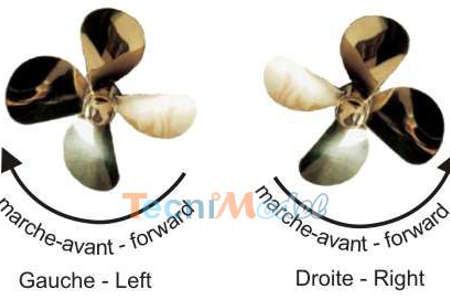

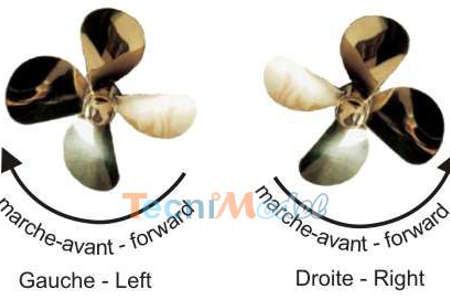

Determining the direction of the propeller wash effect

By convention, the direction of the propeller wash effect is defined in forward gear. For example, a "left-handed" propeller wash effect will have a right-handed effect in reverse, and vice versa.

1-Stop the boat facing the wind or with the wind at the stern.

2-Engage the throttle with a “whiplash” move* in reverse gear.

3-Observe the direction the boat turns: if the stern moves to the left, the wash effect is left-handed in reverse, and vice versa.

*The “whiplash” consists of giving a quick burst of throttle in reverse or forward gear (up to approximately 1800-2000 RPM) and then returning to neutral. This allows you to maneuver using the propeller wash effect without gaining speed.

Performing a U-turn on the spot

Most of the time, there isn’t enough room in ports to make a U-turn solely in forward or reverse gear. It must be done in stages: the available space in front of and behind the boat determines the number of forward and reverse moves needed to complete the U-turn.

For a left-handed propeller wash effect in reverse:

-Turn the rudder toward the desired direction in forward gear.

-Give a burst of throttle in forward gear.

-Return to neutral before the boat gains speed.*

-Give a whiplash move in reverse gear: the boat turns left in reverse thanks to the propeller wash effect (no need to adjust the rudder, as the boat isn’t moving fast enough for the rudder and keel to engage the water flow).

-Continue alternating forward and reverse moves until the U-turn is complete.

*Speed is always dangerous in a port, as it prevents you from stopping your boat quickly if needed.

Nota bene: Always favor a U-turn with the reverse propeller wash effect on the windward side of the boat.

For example, if your propeller wash effect is left-handed in reverse, the boat will turn much better with the wind coming from port (port tack).

1-The skipper must take time to analyze the situation by observing the water: What space does my sailboat or motorboat need to occupy? How are the wind and current? What constraints will I have to deal with, etc.?

2-Choose a strategy

3-Explain the maneuver to the crew

4-Prepare the boat (lines, fenders) and position the crew

5-Action!

Docking at the pontoon with engine power (approach)

-Place fenders along the hull at pontoon height

-Move the boat four to five lengths (of the boat) away from the pontoon

-Align the boat on a trajectory approximately 30° to the pontoon

-Aim for the part of the pontoon where the stern will be positioned once the boat is stopped

-Adjust the speed to stay under 1.5 knots to maintain control and stop the boat easily

-Position someone at the shrouds to assist the helmsperson in gauging distances upon arrival

-In the final meters, gradually bring the side of the boat closer to the pontoon by alternating the rudder to the left and right (S-shaped trajectory)

-Stop the boat parallel to the pontoon using reverse gear

-Disembark crew members near the shrouds

-Moor the boat

Nota bene: Never persist with a poorly executed maneuver. It’s better to start over with a clean approach!

Mooring lines

Two main types of mooring lines exist:

Bow/stern lines are short mooring lines located at the front and back of the boat. They keep the boat parallel to the pontoon. Since the hull is rounded, the middle of the boat presses against the pontoon, so this is where the most fenders are placed. Bow/stern lines should be slightly loose to prevent fenders from being crushed against the pontoon.

Spring lines are longer mooring lines running from the front and back of the boat toward the middle of the pontoon. They prevent the boat from moving forward or backward. The spring line attached to the bow is called a forward spring, while the one at the stern is called an aft spring.

Nota bene: Mooring lines should be untied starting with the loosest ones (those that aren’t holding tension).

Case #1: The wind pushes the boat against the pontoon

Arrival

Even if you stop your boat far from the pontoon, the wind will push you against it. This is the easiest case for an arrival.

Departure

To leave, you must move the boat away from the pontoon to avoid scratching the hull.

In this case, use a forward or aft spring line to pivot the boat around the hull's curvature. Choose a forward spring departure if the wind is coming from the stern or an aft spring departure if the wind is from the bow.

Forward spring departure

-Place fenders from the middle of the boat to the bow. If possible, assign a crew member with a handheld fender to protect the bow ("flying fender").

-Pass the forward spring line around a cleat on the pontoon and return it to the bow so it can be released from the boat.

-Remove other mooring lines.

-Engage forward gear gently, rudder straight, until the spring line tightens.

-Steer toward the pontoon. The bow fenders absorb the pressure, and the stern moves away.

-In strong winds, increase throttle to help move the stern away.

-Once the boat is at a 45° angle to the pontoon, shift to neutral, then reverse gently.

-Retrieve the spring line on board.

-Ensure the boat is far enough from the pontoon before moving forward.

-Engage forward gear and proceed.

Aft spring departure

The aft spring departure is similar in reverse. Use reverse gear until the stern is at a 45° angle to the pontoon, supported by aft fenders.

Case #2: The wind pushes the boat away from the pontoon

Arrival

When you stop your boat, the wind will push it away from the pontoon. You should:

-Stop the boat close enough for crew to disembark.

-Instruct crew to be ready to disembark and secure the boat.

Departure

This time, it’s easier because the wind pushes you away! Simply release spring and bow/stern lines and let the wind carry the boat off.

Tip: Release bow/stern lines from the boat.

Case #3: The wind blows along the pontoon

In this case, always approach into the wind (or current, if stronger) to slow the boat effectively.

In moderate wind, moor using bow/stern lines first, followed by spring lines.

In strong headwind or current, begin with an aft spring and a bow line, followed by other lines.

In strong tailwind or current, begin with a forward spring and a stern line, followed by other lines.

- In ports, speed is a danger factor

- Wind pushing the boat against the pontoon: easy arrival, departure with a forward or aft spring

- Wind pushing the boat away from the pontoon: tricky arrival, easy departure

- It’s always better to arrive facing the wind (or the current if stronger) to stop the boat easily

The Mediterranean case: mooring with lazy lines

Most collisions between recreational boats occur during harbor maneuvers.

Fellow sailors, here’s a recap of the basics of engine maneuvers... Practice them until you master them perfectly!

The propeller wash effect, friend or foe?

A fundamental element of engine maneuvers, the propeller wash effect is the lateral influence of the propeller’s rotation on the boat’s movement. It is always stronger in reverse gear and must be considered during maneuvers.

The principle

A propeller works due to the inclination of its blades. This inclination causes every propeller to push water obliquely.

In forward motion, the propeller pushes water onto the rudder, which, through its orientation, compensates for the lateral effect of the propeller.

In reverse, the propeller pushes water forward, and there’s no rudder to reduce this lateral effect: the boat moves diagonally until the speed is sufficient for the rudder and keel (or centerboard) to engage the water and allow steering.

Thus, the propeller wash effect is strongest in reverse. You must always account for this during engine maneuvers.

Determining the direction of the propeller wash effect

By convention, the direction of the propeller wash effect is defined in forward gear. For example, a "left-handed" propeller wash effect will have a right-handed effect in reverse, and vice versa.

1-Stop the boat facing the wind or with the wind at the stern.

2-Engage the throttle with a “whiplash” move* in reverse gear.

3-Observe the direction the boat turns: if the stern moves to the left, the wash effect is left-handed in reverse, and vice versa.

*The “whiplash” consists of giving a quick burst of throttle in reverse or forward gear (up to approximately 1800-2000 RPM) and then returning to neutral. This allows you to maneuver using the propeller wash effect without gaining speed.

Performing a U-turn on the spot

Most of the time, there isn’t enough room in ports to make a U-turn solely in forward or reverse gear. It must be done in stages: the available space in front of and behind the boat determines the number of forward and reverse moves needed to complete the U-turn.

For a left-handed propeller wash effect in reverse:

-Turn the rudder toward the desired direction in forward gear.

-Give a burst of throttle in forward gear.

-Return to neutral before the boat gains speed.*

-Give a whiplash move in reverse gear: the boat turns left in reverse thanks to the propeller wash effect (no need to adjust the rudder, as the boat isn’t moving fast enough for the rudder and keel to engage the water flow).

-Continue alternating forward and reverse moves until the U-turn is complete.

*Speed is always dangerous in a port, as it prevents you from stopping your boat quickly if needed.

Nota bene: Always favor a U-turn with the reverse propeller wash effect on the windward side of the boat.

For example, if your propeller wash effect is left-handed in reverse, the boat will turn much better with the wind coming from port (port tack).

1-The skipper must take time to analyze the situation by observing the water: What space does my sailboat or motorboat need to occupy? How are the wind and current? What constraints will I have to deal with, etc.?

2-Choose a strategy

3-Explain the maneuver to the crew

4-Prepare the boat (lines, fenders) and position the crew

5-Action!

Docking at the pontoon with engine power (approach)

-Place fenders along the hull at pontoon height

-Move the boat four to five lengths (of the boat) away from the pontoon

-Align the boat on a trajectory approximately 30° to the pontoon

-Aim for the part of the pontoon where the stern will be positioned once the boat is stopped

-Adjust the speed to stay under 1.5 knots to maintain control and stop the boat easily

-Position someone at the shrouds to assist the helmsperson in gauging distances upon arrival

-In the final meters, gradually bring the side of the boat closer to the pontoon by alternating the rudder to the left and right (S-shaped trajectory)

-Stop the boat parallel to the pontoon using reverse gear

-Disembark crew members near the shrouds

-Moor the boat

Nota bene: Never persist with a poorly executed maneuver. It’s better to start over with a clean approach!

Mooring lines

Two main types of mooring lines exist:

Bow/stern lines are short mooring lines located at the front and back of the boat. They keep the boat parallel to the pontoon. Since the hull is rounded, the middle of the boat presses against the pontoon, so this is where the most fenders are placed. Bow/stern lines should be slightly loose to prevent fenders from being crushed against the pontoon.

Spring lines are longer mooring lines running from the front and back of the boat toward the middle of the pontoon. They prevent the boat from moving forward or backward. The spring line attached to the bow is called a forward spring, while the one at the stern is called an aft spring.

Nota bene: Mooring lines should be untied starting with the loosest ones (those that aren’t holding tension).

Case #1: The wind pushes the boat against the pontoon

Arrival

Even if you stop your boat far from the pontoon, the wind will push you against it. This is the easiest case for an arrival.

Departure

To leave, you must move the boat away from the pontoon to avoid scratching the hull.

In this case, use a forward or aft spring line to pivot the boat around the hull's curvature. Choose a forward spring departure if the wind is coming from the stern or an aft spring departure if the wind is from the bow.

Forward spring departure

-Place fenders from the middle of the boat to the bow. If possible, assign a crew member with a handheld fender to protect the bow ("flying fender").

-Pass the forward spring line around a cleat on the pontoon and return it to the bow so it can be released from the boat.

-Remove other mooring lines.

-Engage forward gear gently, rudder straight, until the spring line tightens.

-Steer toward the pontoon. The bow fenders absorb the pressure, and the stern moves away.

-In strong winds, increase throttle to help move the stern away.

-Once the boat is at a 45° angle to the pontoon, shift to neutral, then reverse gently.

-Retrieve the spring line on board.

-Ensure the boat is far enough from the pontoon before moving forward.

-Engage forward gear and proceed.

Aft spring departure

The aft spring departure is similar in reverse. Use reverse gear until the stern is at a 45° angle to the pontoon, supported by aft fenders.

Case #2: The wind pushes the boat away from the pontoon

Arrival

When you stop your boat, the wind will push it away from the pontoon. You should:

-Stop the boat close enough for crew to disembark.

-Instruct crew to be ready to disembark and secure the boat.

Departure

This time, it’s easier because the wind pushes you away! Simply release spring and bow/stern lines and let the wind carry the boat off.

Tip: Release bow/stern lines from the boat.

Case #3: The wind blows along the pontoon

In this case, always approach into the wind (or current, if stronger) to slow the boat effectively.

In moderate wind, moor using bow/stern lines first, followed by spring lines.

In strong headwind or current, begin with an aft spring and a bow line, followed by other lines.

In strong tailwind or current, begin with a forward spring and a stern line, followed by other lines.

- In ports, speed is a danger factor

- Wind pushing the boat against the pontoon: easy arrival, departure with a forward or aft spring

- Wind pushing the boat away from the pontoon: tricky arrival, easy departure

- It’s always better to arrive facing the wind (or the current if stronger) to stop the boat easily